|

Continuing our series of the different parts of the Mass, we now turn to the summit of the liturgy, the Eucharistic Prayer.The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) describes it as follows:

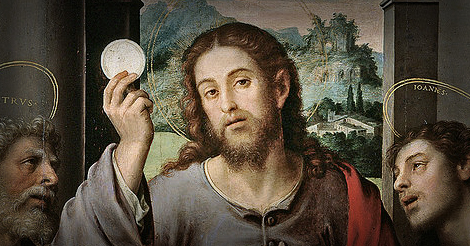

“Now the center and summit of the entire celebration begins: namely, the Eucharistic Prayer, that is, the prayer of thanksgiving and sanctification. The priest invites the people to lift up their hearts to the Lord in prayer and thanksgiving; he unites the congregation with himself in the prayer that he addresses in the name of the entire community to God the Father through Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit. Furthermore, the meaning of the Prayer is that the entire congregation of the faithful should join itself with Christ in confessing the great deeds of God and in the offering of Sacrifice. The Eucharistic Prayer demands that all listen to it with reverence and in silence.”This is an element of the Mass that is recited entirely by the priest, with occasional acclamations voiced by the faithful. The priest, in this capacity, is acting in persona christi, or “in the person of Christ” allowing God to work through him to bring about the miracle of the Eucharist. The Catechism explains: “Christians come together in one place for the Eucharistic assembly. At its head is Christ himself, the principal agent of the Eucharist. He is high priest of the New Covenant; it is he himself who presides invisibly over every Eucharistic celebration. It is in representing him that the bishop or priest acting in the person of Christ the head (in persona Christi capitis) presides over the assembly, speaks after the readings, receives the offerings, and says the Eucharistic Prayer” (CCC 1328) The faithful kneel during the Eucharistic Prayer in preparation for witnessing the coming of Christ the King, kneeling before Him in adoration and expectation. The actions of the priest, too, are very symbolic, each part referring to the great mystery unfolding. Here is how the GIRM explains each part of the Eucharistic Prayer: “The chief elements making up the Eucharistic Prayer may be distinguished in this way:

This time is meant to prepare us to receive our Lord in the Holy Eucharist and to witness His coming as the bread and wine are transformed into His body and blood. It is not a mere symbol, but a truth that is beyond words. The next time we go to Mass, let us pray the words of the father of the son possessed by a demon, ”I believe; help my unbelief! (Mark 9:24) The Mass is indeed a great mystery and we need God’s help to better understand what is truly happening before our eyes! Read the Entire Series

0 Comments

To continue our series on the different parts of the Mass, we will now examine the beginning of the Liturgy of the Eucharist and in particular, the "Sanctus" or "Holy, Holy, Holy."

We now enter into the second part of the divine liturgy, which is called the "Liturgy of the Eucharist." This is the part of the Mass where the words that were spoken at the Gospel become Flesh in the Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist. As the GIRM narrates for us the significance of this part of the Mass, "At the Last Supper Christ instituted the Paschal Sacrifice and banquet by which the Sacrifice of the Cross is continuously made present in the Church whenever the priest, representing Christ the Lord, carries out what the Lord himself did and handed over to his disciples to be done in his memory. "For Christ took the bread and the chalice and gave thanks; he broke the bread and gave it to his disciples, saying, 'Take, eat, and drink: this is my Body; this is the cup of my Blood. Do this in memory of me.' Accordingly, the Church has arranged the entire celebration of the Liturgy of the Eucharist in parts corresponding to precisely these words and actions of Christ:

At the start of the Liturgy of the Eucharist there is the Preparation of the Gifts, where the gifts to be sacrificed are given to the priest. In historical context, members of the early Church would bake the bread and create the wine needed for the celebration. They would then bring those elements and offer them to the priest. This is why we currently have the custom in the Church to select representatives from the congregation to present the bread and wine to be consecrated, symbolizing the offering of ourselves to God. After the gifts are prepared at the altar by the priest, the "Santcus" (Holy, Holy, Holy) is intoned and all kneel in preparation for the greatest miracle of all times: God humiliates Himself so much as to dwell in a simple piece of bread and a small chalice of wine. Historically, "not every one of the ancient liturgies knew this [particular] hymn, although its institution is attributed to St. Sixtus I who, as Pope, introduced it into the Mass in the second century" (TM). In the current translation of the Mass, the Sanctus has a slight revision that better expresses the mystery that it is meant to teach us. "The opening line of the Sanctus is taken not from a hymn book, but from the angel's worship of God in heaven. In the Old Testament, the prophet Isaiah was given a vision of the angels praising God, crying out: 'Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts' (see Isaiah 6:3). The word 'hosts' here refers to the heavenly army of angels. When we recite 'Holy, Holy, Holy Lord' in the Mass, therefore, we are joining the angels in heaven, echoing their very words of worship. The previous translation of this prayer referred to the Lord as 'God of power and might.' In the new translation, we address him as 'Lord God of Hosts.' This more clearly echoes the biblical language of the angels in Isaiah and underscores the infinite breadth of God's power" (TM). When we said "God of power and might," it was more abstract, while when we say "Lord God of Hosts," it is more concrete and specific, referring to the heavenly "hosts" of angels, archangels, principalities, virtues, powers, dominions, thrones, cherubim and seraphim; in other words, the entire heavenly army! This ancient hymn prepares us for what is about to unfold and reminds us that we are never alone at Mass. The angels surround us and sing with us a "hymn of praise!" Mass is a meeting place of Heaven and Earth and so we must prepare ourselves for the great mystery that occurs in front of our eyes! Read the Entire Series

To continue our series on the different parts of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, we conclude our look at the Introductory Rites with “The Collect” (aka the Opening Prayer) and then move on to take a look at the “Liturgy of the Word”

“Next the priest invites the people to pray. All, together with the priest, observe a brief silence so that they may be conscious of the fact that they are in God’s presence and may formulate their petitions mentally. Then the priest says the prayer which is customarily known as the Collect and through which the character of the celebration is expressed. In accordance with the ancient tradition of the Church, the collect prayer is usually addressed to God the Father, through Christ, in the Holy Spirit, and is concluded with a trinitarian…ending.” (GIRM) Besides being rich in theological meaning the Opening Prayer has a long history that goes all the way back to ancient Rome. “Historically that title (Collect) recalls the old custom of Urban Rome where, about the fourth century, it was the practice for the whole Christian community to come together in one church that they might proceed with solemnity to the sanctuary chosen for the celebration of the day’s Mass; in this sense the Collect is the prayer of the plebs collecta, the prayer of the assembled people.” (TM) Today, the priest gathers “together, as if in one sheaf, all our hopes and all our good purposes…to offer them to God” and so continues this tradition of a unified prayer of the people at the start of every Mass. After the Collect, starts the “Liturgy of the Word.” “The main part of the Liturgy of the Word is made up of the readings from Sacred Scripture together with the chants occurring between them. The homily, Profession of Faith, and Prayer of the Faithful, however, develop and conclude this part of the Mass. For in the readings, as explained by the homily, God speaks to his people, opening up to them the mystery of redemption and salvation and offering them spiritual nourishment; and Christ himself is present in the midst of the faithful through his word. By their silence and singing the people make God’s word their own, and they also affirm their adherence to it by means of the Profession of Faith. Finally, having been nourished by it, they pour out their petitions in the Prayer of the Faithful for the needs of the entire Church and for the salvation of the whole world.” (GIRM) The history behind the Liturgy of the Word is very ancient and even extends before the Christian Church began. To “seek the origin of these readings, we would have to delve into the most ancient of Christian usages, and to go, in fact, even beyond them to practices dear to the heart of devout Israel. The Service of the synagogue knew such readings from the Law and the Prophets. Have we not seen Jesus reading Isaias to his fellow Jews (Luke 4:16,21)? The early church faithfully preserved this usage: reading from the sacred books bulked large in the primitive liturgies, and it would be surprising to the first Christians were they now to return and hear only the…brief scraps which are left in today’s Mass. “At first, these readings were neither brief nor formally delimited beforehand…and the reader used to go on uninterruptedly until the bishop saw fit to signal him that he thought enough had been proposed for the instruction of his hearers. It was only with the appearance of the Roman Missal of 1570 that there came into general usage the…previously selected fragments…accommodated to the feast being celebrated.” (TM) In the Liturgy of the Word, we start out by first hearing a reading from the Old Testament, and then a reading from an Apostolic Letter, and then finally we reach a selection from one of the Gospels. The reasoning behind this is simple: “it shows that in the beginning God speaks to us by the agency of intermediaries, by the mouth of men who are His witnesses or confessors, who are inspired by Him to prepare us that we may later receive His own message directly.” (TM) The Liturgy of the Word allows us to hear God’s word to us and prepares us to meet him in the Holy Eucharist. Read the Entire Series

To continue our series on the different parts of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, we continue to examine the Introductory Rites and take a look what is commonly known as the "Kyrie" and "Gloria.”

"After the Act of Penitence, the Kyrie is always begun, unless it has already been included as part of the Act of Penitence. Since it is a chant by which the faithful acclaim the Lord and implore his mercy, it is ordinarily done by all, that is, by the people and with the choir or cantor having a part in it." (GIRM) The Kyrie and the Gloria have been a part of the preparation to celebrate the Divine Mysteries of God since the very beginning. "The Kyrie [Lord have Mercy] is a remnant of those litanic dialogues, of those acclamatory prayers, which rose up spontaneously in the breast of the primitive Church. It originated in the Greek-speaking East, perhaps in Jerusalem where [it was heard] sung [in] about the year 500 [AD]. [The Kyrie] carries to the Three Divine Persons in turn, our heartfelt need and purposive desire for salvation." (This is the Mass (TM), 44) The Kyrie and Gloria express two desires that arise in the hearts of man. "To give glory to God and to beg His mercy are the two purposes which link man to God: it is because we know that God is Almighty that we beseech Him to have mercy upon us." (TM, 44) In other words, we recognize that because God is glorious and worthy of praise (Gloria), we seek his forgiveness (Kyrie) before daring to enter into His dwelling place. Immediately following the Kyrie, "there is intoned a hymn to the Majesty of God." (TM, 44) "The Gloria is a very ancient and venerable hymn in which the Church, gathered together in the Holy Spirit, glorifies and entreats God the Father and the Lamb. The text of this hymn may not be replaced by any other text...It is sung or said on Sundays outside the Seasons of Advent and Lent, on solemnities and feasts, and at special celebrations of a more solemn character." (GIRM) Historically speaking, the Gloria has been a part of the Church since the very beginning: "The Gloria is a very old prayer, already in existence in the second century, which was incorporated into the Roman Mass in the sixth century. It opens appropriately with the words in which the angels sang praise 'to God in the highest;' for is not every Mass a renewal, in some sense, of Christmas, and does it not mark, once more, the Coming of Our Lord? " (TM, 44) The words of the Gloria are rich in meaning, and start out with the words of the angels at the birth of Christ, "Glory to God in the Highest..." (see Luke 2:14) The remaining words were picked deliberately to help convey our own hearts thankfulness to God and our understanding of who He is. The deep meaning of the words can be seen especially in the recent translation of the Mass texts: "In the [recent] translation [of the Mass], Jesus is addressed as the 'Only Begotten Son.' This more closely follows the theological language used in the early Church to highlight how Jesus is uniquely God's Son, sharing in the same divine nature as the Father. This also reflects the biblical language in John's gospel, which uses similar wording to describe Jesus' singular relationship with the Father." (A Guide to the New Translation of the Mass, 12) As we progress through the Mass, let us remember that the Mass is ultimately a prayer of thanksgiving that gives honor and glory to God. Attending Mass gives us the opportunity to praise Him and recognize His presence in our lives. He is the Creator of the Universe and more importantly, the Creator of us! We owe everything to God and so it is "right and just" that we praise Him with every fiber of our being! Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will. We praise you, we bless you, we adore you, we glorify you, we give you thanks for your great glory. Lord God, heavenly King, O God, almighty Father. Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son, Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us; you take away the sins of the world, receive our prayer; you are seated at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us. For you alone are the Holy One, you alone are the Lord, you alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father, Amen. Read the Entire Series

To continue our series on the different parts of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, we continue to examine the Introductory Rites and take a look at the "The Penitential Rite.”

"Then the priest invites those present to take part in the Act of Penitence, which, after a brief pause for silence, the entire community carries out through a formula of general confession. The rite concludes with the priest's absolution, which, however, lacks the efficacy of the Sacrament of Penance." (GIRM, 51) The history of asking for forgiveness at the start of Mass is very long and rich and started with Christ at the Last Supper: "In the primitive Church, which had its roots in the heart of Christ, there was a spontaneous sense of the soul's need to ask for pardon at the beginning of Mass. (And, indeed, it seems that there may have then existed a penitential rite like the washing of the disciple's feet by Jesus before the Last Supper.) "The Roman Missal as drawn up in 1570 [formalized the need to ask pardon before Mass and] constructed [the rite] in the dramatic manner associated with the four states of a trial:the soul appears before the bar of justice, the soul confesses its guilt, the advocates plead, and pardon is granted. This is a public collective prayer in which priest and people...acknowledge their sinfulness, not just privately, but in the face of the whole Church, of all her saintly witnesses, and even in the face of the very powers of Heaven." (This is the Mass, 32) The current translation of the Penitential Rite not only "better reflects the Latin text of the Mass [it also]helps us cultivate a more humble, sorrowful attitude toward God as we confess our sins. Instead of simply saying that I have sinned 'through my own fault' as we have in the old translation, we...now repeat it three times while striking our breasts in a sign of repentance, saying 'Through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.' This repetition more fully expresses our sorrow over sin...This prayer in the liturgy helps us recognize that sinning against God is no light matter. We must take responsibility for whatever wrong we have done and whatever good we failed to do." (A Guide to the New Translation of the Mass, 11) Henri Daniel-Rops describes the symbolism of the Penitential Rite best when he writes: “The thrice repeated act of deep repentance, at [through my fault], when the hand strikes the breast in an old biblical and monastic gesture, brings consolation to the sinner in his racking sorrow; for is it not written that the prayer of the humble shall be heard before the Most High? (Ecclus. 35:21) (This is the Mass, 32) The next time you attend Mass and recite these words, envision yourself at the Last Supper, begging pardon from Jesus, before he hand you the bread that is His body. I confess to almighty God, and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have greatly sinned in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, [strike breast while saying] through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, to pray for me to the Lord our God. Read the Entire Series

“The Eucharist is ‘the source and summit of the Christian life.’”The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it. For in the blessed Eucharist is contained the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ himself, our Pasch.”

“[The Eucharist] is the culmination both of God’s action sanctifying the world in Christ and of the worship men offer to Christ and through him to the Father in the Holy Spirit.” “Finally, by the Eucharistic celebration we already unite ourselves with the heavenly liturgy and anticipate eternal life, when God will be all in all.” (CCC 1324-26) The celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass has been “the source and summit” of our lives as Catholics ever since Christ’s sacrifice upon the Cross. As a result, it is “right and just” to put emphasis on the celebration of such great a mystery that unites us to the cross of Christ and to heaven itself. Unfortunately, many of us do not understand the gravity of a Mass and how it can truly change our lives. It is easy to get caught “going through the motions” and so that is why we will be spending the next few weeks explaining the vital importance of the Mass and taking you step by step into the most profound meeting of heaven and earth. We will start at the beginning of Mass, with what is called the “Introductory Rites.” “The rites preceding the Liturgy of the Word, namely the Entrance, Greeting, Act of Penitence, Kyrie, Gloria, and Collect, have the character of a beginning, introduction, and preparation. Their purpose is to ensure that the faithful who come together as one establish communion and dispose themselves to listen properly to God’s word and to celebrate the Eucharist worthily.” (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, GIRM 46) The Entrance: ”After the people have gathered, the Entrance chant begins as the priest enters with the deacon and ministers.” (GIRM, 47) This entrance procession before the liturgy begins has a rich history as is related by Henri-Daniel Rops: “In the early days of the Roman Church, the Pope went from the Lateran Palace in a solemn cortege of his attendant clergy, deacons, and acolytes, to the particular sanctuary in which Mass was, that day, to be said…In it lies the origin of the processional entrance. Psalms were chanted by alternating choirs…psalms which were specially chosen for their consonance with the underlying intention of the particular day’s sacrifice….Thus the Introit [also called the Entrance Antiphon] became an entrance-song…which, by a few brief words, states the theme or point of emphasis of the Mass.” (This is the Mass, 40) Currently in the Church we retain the tradition of reciting or singing a psalm as the “Entrance Antiphon” which is based on the theme for the Mass of the day. In the GIRM, there are four options that are permissible to celebrate the entrance procession: (1) the antiphon from the Roman Missal or the Psalm from the Roman Gradual as set to music there or in another musical setting; (2) the seasonal antiphon and Psalm of the Simple Gradual; (3) a song from another collection of psalms and antiphons, approved by the Conference of Bishops; (4) a suitable liturgical song similarly approved by the Conference of Bishops or the Diocesan Bishop. If there is no singing at the entrance, the antiphon in the Missal is recited either by the faithful, or by some of them, or by a lector.” Regardless of what option is selected, the hope is that the selection will reflect the theme of the day, often based on the readings at Mass. This helps those present at Mass to prepare and presents a sort of “prelude” to the readings that will be read. Read the Entire Series

Often when we go to Mass it is easy to slip into the habit of "going through the motions."

We stand. We sit. We kneel. We leave. Nothing much changes week-to-week, besides some extra flowers and maybe a different color. What is the whole point? Why do we we stand, sit, kneel and receive Holy Communion? In order to answer that question, over the next several weeks we will be walking through the Mass, going through the symbolism that is present in the celebration. Hopefully this will open your eyes anew to this ancient liturgy and will help you stop "going through the motions" and recognize that you are participating in something much greater than yourselves. In fact, what you are doing today at Sunday Mass is not much different than what the early Christians did in the 2nd century, almost 2,000 years ago! If you want evidence, here is a passage from Saint Justin Martyr, who wrote in 155 AD about the common celebration of the liturgy: "No one may share the Eucharist with us unless he believes that what we teach is true, unless he is washed in the regenerating waters of baptism for the remission of his sins, and unless he lives in accordance with the principles given us by Christ. "On Sunday we have a common assembly of all our members, whether they live in the city or the outlying districts. The recollections of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as there is time. When the reader has finished, the president of the assembly speaks to us; he urges everyone to imitate the examples of virtue we have heard in the readings. Then we all stand up together and pray. "On the conclusion of our prayer, bread and wine and water are brought forward. The president offers prayers and gives thanks to the best of his ability, and the people give assent by saying, “Amen”. The eucharist is distributed, everyone present communicates, and the deacons take it to those who are absent. "The wealthy, if they wish, may make a contribution, and they themselves decide the amount. The collection is placed in the custody of the president, who uses it to help the orphans and widows and all who for any reason are in distress, whether because they are sick, in prison, or away from home. In a word, he takes care of all who are in need. "We hold our common assembly on Sunday because it is the first day of the week, the day on which God put darkness and chaos to flight and created the world, and because on that same day our savior Jesus Christ rose from the dead. For he was crucified on Friday and on Sunday he appeared to his apostles and disciples and taught them the things that we have passed on for your consideration." Did anything sound familiar? Look back and see if you can identify these part of the Mass: Introductory Rites - Penitential Rite Liturgy of the Word -Readings -Homily -Profession of Faith -Collection Liturgy of the Eucharist -Presentation of the Gifts and Preparation of the Altar -Prayer over the Offerings -Eucharistic Prayer -Reception of Communion -Dismissal Over the next several weeks we will dive into each part of the Mass and discover the symbolism behind the ancient rites and discover the beauty and glory of the Mass anew.

Throughout the liturgical year, a Catholic will notice there are a few "Holy Days of Obligation." Typically when someone sees or hears that phrase they simply know, "I have to go to Mass on that day."

But why? Isn't going to Mass on Sunday enough? Let's look at what "Holy Days of Obligation" are in order to find out why they are important for us. The Catechism of the Catholic Church offers this initial explanation: "Participation in the communal celebration of the Sunday Eucharist is a testimony of belonging and of being faithful to Christ and to his Church. The faithful give witness by this to their communion in faith and charity. Together they testify to God's holiness and their hope of salvation. They strengthen one another under the guidance of the Holy Spirit" (CCC 2182). "Just as God 'rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done,' human life has a rhythm of work and rest. The institution of the Lord's Day helps everyone enjoy adequate rest and leisure to cultivate their familial, cultural, social, and religious lives." (CCC 2184). "On Sundays and other holy days of obligation, the faithful are to refrain from engaging in work or activities that hinder the worship owed to God, the joy proper to the Lord's Day, the performance of the works of mercy, and the appropriate relaxation of mind and body. " (CCC 2185). Holy Days of Obligation are considered in the Catholic Church an "extension" of the Sabbath; a day devoted to prayer, rest and leisure. In Catholic countries it is often the case that Holy Days of Obligation are also "civil" holidays and businesses are closed on those days in observance of them. In our own country, Christmas is one of those "holy days" that is recognized both in the Church and by the state. Holy Days of Obligation give us an opportunity to reflect on the mystery of Christ in a particular way, focusing on an aspect of our beliefs that is central to who we are as Christians. Christmas is probably the best example of how we are able to focus on a particular aspect of the Christian mystery and extend our "Sabbath rest" on that day. The Church in the United States give us 8 Holy Days of Obligation, but often they are moved to the nearest Sunday to facilitate greater participation. Here they are:

In the end, when we think of Holy Days of Obligation, let us remember that they are extensions of the Sabbath and are meant to be little islands of rest for body and soul in what can often be a strenuous work week. God knows us better than we know ourselves and so we should welcome these holy days as gifts from Him that are meant to refresh us and bring us life. Read the Entire Series

Last week we learned about the celebration of “feast days” in the Church and this we will discover a particular celebration that is no on the calendar, but is an option for each Saturday of the year.

Every Saturday in the Catholic Church (provided there is no other feast of greater importance) is dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. A priest may celebrate a special “votive” Mass on Saturday morning in honor of Our Lady. Bishop Fulton Sheen, for example, insisted that priests celebrate Mass on Saturdays in honor of the Blessed Virgin, which he took very seriously. Our Lady of Fatima requested that the faithful honor her on the First Saturday of each month. But why Saturday? The Marian Catechist Apostolate gives this reasoning based on historical research: "Saturday is the day when creation was completed; therefore it is also celebrated as the day of the fulfillment of the plan of salvation, which found its realization through Mary. Sunday is the Lord’s Day, so it seemed appropriate to observe the preceding day as Mary’s day. In addition, as Genesis describes, God rested on the seventh day, Saturday. The seventh day, and the Jewish Sabbath, is Saturday; we rest on Sunday, because we celebrate the Resurrection as our Sabbath Day. In parallel, Jesus rested in the womb and then in the loving arms of Mary from birth until she held His lifeless body at the foot of the Cross; thus the God-head rested in Mary." The Vatican’s Directory on Popular Piety supplements the above explanation and gives this account: "188. Saturdays stand out among those days dedicated to the Virgin Mary. These are designated as memorials of the Blessed Virgin Mary(218). This memorial derives from carolingian time (ninth century), but the reasons for having chosen Saturday for its observance are unknown. While many explanation have been advanced to explain this choice, none is completely satisfactory from the point of view of the history of popular piety. Prescinding from its historical origins, to-day the memorial rightly emphasizes certain values 'to which contemporary spirituality is more sensitive: it is a remembrance of the maternal example and discipleship of the Blessed Virgin Mary who, strengthened by faith and hope, on that great Saturday on which Our Lord lay in the tomb, was the only one of the disciples to hold vigil in expectation of the Lord’s resurrection; it is a prelude and introduction to the celebration of Sunday, the weekly memorial of the Resurrection of Christ; it is a sign that the “Virgin Mary is continuously present and operative in the life of the Church.' Popular piety is also sensitive to the Saturday memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The statutes of many religious communities and associations of the faithful prescribe that special devotion be paid to the Holy Mother of God on Saturdays, sometimes through specified pious exercises composed precisely for Saturdays." Saturday is a great day to honor our Blessed Mother and if we are not able to go to morning Mass where it is offered, we can always pray a rosary or another Marian prayer to honor her. She is our spiritual mother and deserves our love and devotion (as do all mothers) and so dedicating an entire day of the week to her is most fitting. Read the Entire Series

News from the USCCB

U.S. Bishop Delegation To Join Bishops Of The Americas In Mercy Congress - WASHINGTON—A delegation of U.S. bishops led by Archbishop Joseph E. Kurtz, USCCB president, will join bishops from the Americas and the Caribbean in a jubilee gathering to celebrate the Year of Mercy in Bogota, Colombia, August 27-30. The gathering of bishops, clergy, religious and lay leaders, titled the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy on the American Continent was organized by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America and the Latin-American Episcopal Conference in conjunction with the bishops of the United States and Canada, and the Knights of Columbus. ..Read More News from the Pope: Migrants and refugees at the heart of Pope's new 'Motu Proprio' - (Vatican Radio) Pope Francis has created a new Dicastery to better minister to the needs of the men and women the Church is called to serve. The new “Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development” was instituted in aMotu Proprio published on Wednesday in the Osservatore Romano. ....Read More News from the Church: Mother Teresa’s Personal Touch - An encounter with Mother Teresa of Kolkata has a lasting impact. In the days leading up to her Sept. 4 canonization in Rome, three of those who knew her personally recalled how their meetings with the saintly sister changed the direction of their lives. Jim Towey, the president of Ave Maria University in Ave Maria, Fla., is a former assistant to President George W. Bush and director of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. Before that, while working for Sen. Mark Hatfield, R-Ore., on assignment in the Far East, he met Mother Teresa.“Thirty-one years ago, the Lord gave me the grace of meeting her, and it changed my life,” Towey said. “I met her the week she turned 75. When I met Mother Teresa that day in August 1985, I saw a person who was everything I wasn’t. She was so alive in Christ, so given to others.”.....Read more |

MASS SCHEDULE

Tuesday - Friday: 8:00 AM Saturday: 4:00 PM Sunday: 8:00 AM & 10:00 AM RECONCILIATION

Saturday: 3:15 - 3:45 PM OFFICE HOURS

Monday - Thursday: 8:30 AM – 5:00 PM Friday: 8:30 AM – 12:30 PM Stay Connected with Our ParishWelcome from Our PastorWelcome to Christ the King Catholic Church! Ever since 1938 this parish has been assisting souls in their quest for deeper union with God. Our mission statement is essentially found in the stained glass window above the main altar: “For Christ our King.” Insofar as God made us and we belong to Him, we have come to... Read More

Archives

February 2021

Categories

All

|

Copyright © 2024 Christ the King Parish. All Rights Reserved.

Mailing address: 306 S. LaSalle St, Spencer, WI 54479

(715) 659-4480

RSS Feed

RSS Feed